Will the Congress Ever Declare War Again

Onorth September one, 1970, shortly after President Nixon expanded the Vietnam War by invading neighboring Cambodia, Democratic Senator George McGovern, a decorated World State of war II veteran and hereafter presidential candidate, took to the floor of the Senate and said,

"Every Senator [hither] is partly responsible for sending 50,000 immature Americans to an early on grave… This chamber reeks of blood… It does not have any backbone at all for a congressman or a senator or a president to wrap himself in the flag and say nosotros are staying in Vietnam, because it is not our blood that is being shed."

More than than six years had passed since Congress all but rubber-stamped President Lyndon Johnson'due south notoriously vague Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which provided what little legal framework at that place was for U.Due south. war machine escalation in Vietnam. Doubts remained equally to the veracity of the supposed North Vietnamese naval attacks on U.S. ships in the Tonkin Gulf that had officially triggered the resolution, or whether the Navy even had cause to venture so close to a sovereign nation's coastline. No matter. Congress gave the president what he wanted: essentially a blank bank check to bomb, batter, and occupy Due south Vietnam. From in that location it was but a few short steps to nine more than years of war, illegal hole-and-corner bombings of Laos and Kingdom of cambodia, ground invasions of both those countries, and eventually 58,000 American and upward of 3 million Vietnamese deaths.

Leaving aside the rest of this state's sad chapter in Indochina, let's simply focus for a moment on the role of Congress in that era's war making. In retrospect, Vietnam emerges as only one more than chapter in 70 years of ineptitude and aloofness on the part of the Senate and Firm of Representatives when information technology comes to their constitutionally granted war powers. Time and again in those years, the legislative co-operative shirked its historic — and legal — responsibility under the Constitution to declare (or refuse to declare) war.

And all the same, never in those seven decades has the duty of Congress to assert itself in matters of war and peace been quite and so vital as information technology is today, with American troops engaged — and still dying, even if now in small numbers — in one undeclared war after some other in Afghanistan, Republic of iraq, Syria, Somalia, Yemen, and now Niger… and who fifty-fifty knows where else.

Fast forrard 53 years from the Tonkin Gulf crunch to Senator Rand Paul'south desperate attempt this September to forcefulness something as simple equally a congressional discussion of the legal footing for America's forever wars, which garnered only 36 votes. It was scuttled by a bipartisan coalition of war hawks. And who fifty-fifty noticed — other than obsessive viewers of C-Span who were treated to Paul's four-hour-longcri de coeur denouncing Congress'due south agreement to "unlimited war, anywhere, anytime, anyplace upon the globe"?

The Kentucky senator sought something that should have seemed modest indeed: to finish the reliance of ane administration later on some other on the long-outdated post-9/11 Authorization for the Utilise of Military Strength (AUMF) for all of America's multifaceted and widespread conflicts. He wanted to hogtie Congress to debate and legally sanction (or not) whatever hereafter military operations anywhere on Globe. While that may sound reasonable enough, more than than 60 senators, Autonomous and Republican alike, stymied the effort. In the procedure, they sanctioned (notwithstanding again) their abdication of any part in America's perpetual country of state of war — other than, of course, funding information technology munificently.

In June 1970, with fifty,000 U.S. troops already expressionless in Southeast Asia, Congress finally worked up the nerve to repeal the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, a bipartisan attempt spearheaded by Senator Bob Dole, the Kansas Republican. As it happens, in that location are no Bob Doles in today'due south Senate. As a result, you hardly accept to exist a carper or a Punxsutawney groundhog to predict six more than weeks of winter — that is, endless war.

It's a remarkably one-time story actually. Ever since V-J Day in August 1945, Congress has repeatedly ducked its explicit constitutional duties when information technology comes to war, handing over the keys to the eternal utilize of the U.S. military to an increasingly royal presidency. An oftentimes deadlocked, ever less popular Congress has cowered in the shadows for decades as Americans died in undeclared wars. Judging by the lack of public outrage, perhaps this is how the citizenry, too, prefers information technology. After all, they themselves are unlikely to serve. There's no draft or need to sacrifice anything in or for America's wars. The public's only task is to stand for increasingly militarized pregame sports rituals and to "thank" whatsoever soldier they run into.

Nonetheless, with the quixotic thought that this is not the manner things have to be, here's a brief recounting of Congress's lxx-year romance with cowardice.

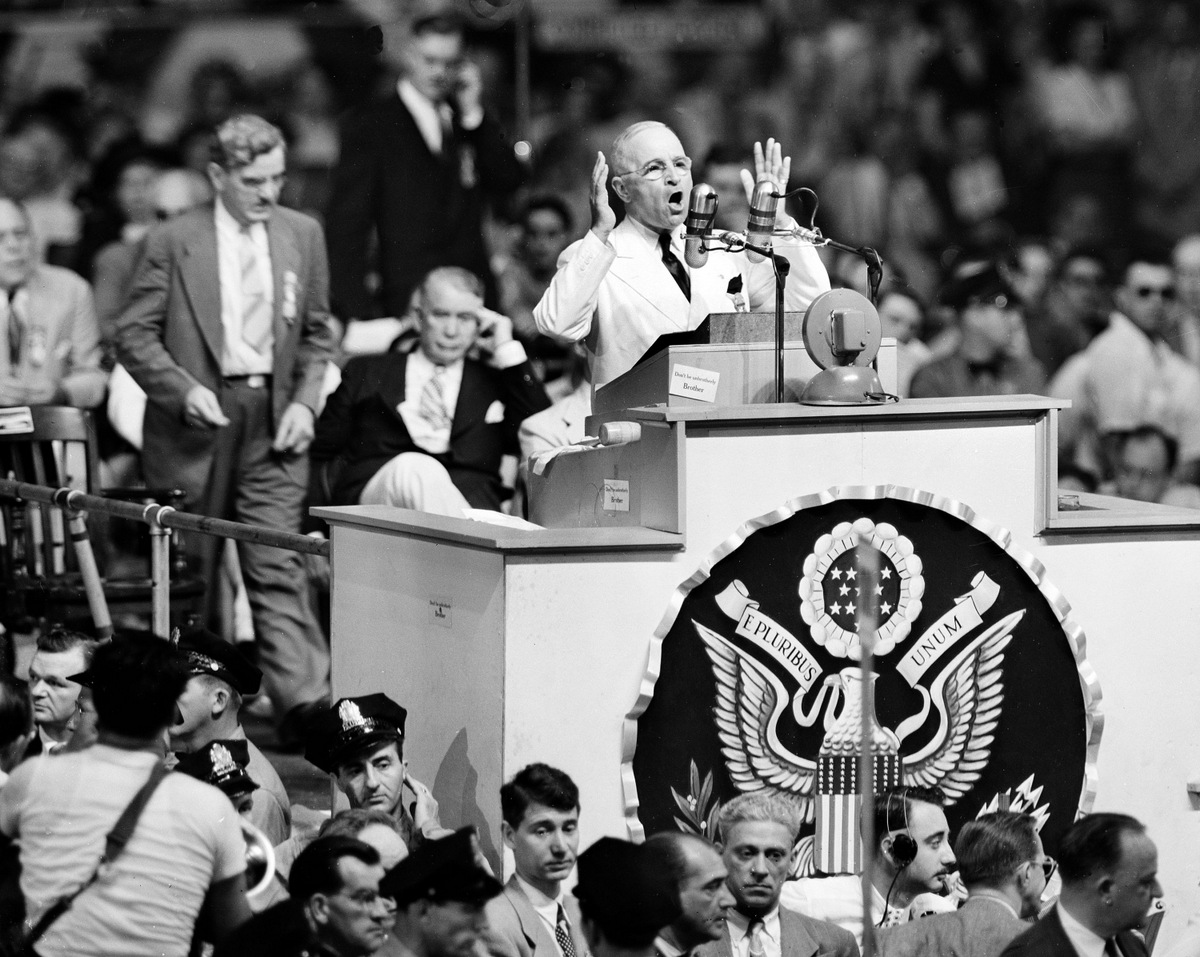

The Korean War

President Harry S. Truman accepts the Democratic presidential nomination in a speech during the Democratic National Convention at Convention Hall in Philadelphia. July 15, 1948. (AP Photo)

The last time Congress actually alleged war, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was president, the Japanese had just attacked Pearl Harbor, and there were Nazis to defeat. V years afterwards the end of World War II, still, in response to a North Korean invasion of the South meant to reunify the Korean peninsula, Roosevelt's successor, Harry Truman, decided to intervene militarily without consulting Congress. He undoubtedly had no idea of the precedent he was setting. In the 67 intervening years, upwards of 100,000 American troops would die in this state'southward undeclared wars and it was Truman who started u.s.a. downwardly this road.

In June 1950, having "conferred" with his secretaries of state and defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he appear an intervention in Korea to halt the invasion from the North. No war declaration was necessary, the administration claimed, because the U.S. was interim under the "custodianship" of a unanimous United Nations Security Council resolution — a nine-0 vote because the Soviets were, at the time, boycotting that body. When asked by reporters whether full-scale gainsay in Korea didn't actually plant a war, the president carefully avoided the term. The conflict, he claimed, only "constituted a police action under the U.North." Fearing that the Soviets might reply by escalating the conflict and that atomic reprisals weren't out of the question, Truman clearly considered information technology prudent to hedge on his terminology, which would set a perilous precedent for the future.

As American casualties mounted and the fighting intensified, it became increasingly difficult to maintain such semantic charades. In iii years of grueling combat, more than 35,000 American troops perished. At the congressional level, it made no divergence. Congress remained essentially passive in the face of Truman'sfait accompli. In that location would be no state of war proclamation and no extended debate on the legality of the president's determination to send gainsay troops to Korea.

Indeed, almost congressmen rallied to Truman's defense in a time of… well, police activeness. At that place was, nonetheless, ane lone voice in the wilderness, one very public congressional dissent. If Truman could commit hundreds of thousands of troops to Korea without a congressional declaration, Republican Senator Robert Taft proclaimed, "he could go to war in Malaya or Republic of indonesia or Iran or South America." As a memory, Taft'south public rebuke to presidential war-making powers is now lost to all merely a few historians, merely how right he was. (And were the Trump administration e'er to go to war with Iran, to pick one of Taft'due south places, count on the fact that it would however be without a congressional proclamation of war.)

Vietnam and the State of war Powers Deed

President Lyndon Johnson, right, talks with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, center sitting, after McNamara returned from a fact-finding trip to South Vietnam, at the White Business firm in Washington, March 13, 1964. (AP Photo)

From the start, Congress condom-stamped President Johnson'due south Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which passed unanimously in the Firm and with only two dissenting Senate votes. Despite many afterward debates and resolutions on Capitol Hill, and certain strikingly disquisitional figures similar Autonomous Senator William Fulbright, most members of Congress supported the president's war powers to the end. Even at the height of congressional anti-war sentiment in 1970, only one in 3 members of the House voted for actual end-the-war resolutions.

According to a specially commissioned House Autonomous Study Group, "Up to the spring of 1973, Congress gave every president everything he requested regarding Indochina policies and funding." Despite enduring myths that Congress "ended the war," every bit late as 1970 the McGovern-Hatfield amendment to the Senate's war machine procurement bill, which called for a U.Due south. withdrawal from Cambodia within 30 days, failed by a vote of 55-39.

Despite some critical voices (of a sort almost completely absent on the subject of American war in the twenty-showtime century), the legislative branch as a collective body discovered far besides late that American military machine forces in Vietnam could never achieve their goals, that Due south Vietnam remained peripheral to whatever imaginable U.Due south. security interests, and that the ceremonious war there was never ours to win or lose. It was a Vietnamese, not an American, story. Unfortunately, past the time Congress collectively gathered the nerve to ask the truly tough questions, the war was on its fifth president and most of its victims — Vietnamese and American — were already dead.

In the summertime of 1970, Congress did finally repeal the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, while also restricting U.S. cross-border operations into Laos and Cambodia. Then, in 1973, over President Richard Nixon's veto, it fifty-fifty passed the War Powers Act. In the time to come, that bill stated, only a congressional declaration of state of war, a national defense force emergency, or "statutory authorisation" past Congress could legally sanction the deployment of the armed services to whatever conflict. Without such sanction, section 4(a)(1) of the neb stipulated that presidential war machine deployments would be subject to a 60-day limit. That, it was then believed, would forever cheque the war-making powers of the imperial presidency, which in turn would prevent "future Vietnams."

In reality, the State of war Powers Deed proved to exist largely toothless legislation. It was never truly accepted by the presidents who followed Nixon, nor did Congress generally have the guts to invoke it in any meaningful manner. Over the terminal 40 years, Democratic and Republican presidents alike have insisted in ane way or another that the War Powers Act was essentially unconstitutional. Rather than fight it out in the courts, however, most administrations simply ignored that constabulary and deployed troops where they wanted anyhow or made dainty and sort of, kind of, mentioned impending armed services interventions to Congress.

Lots of "non-wars" like the invasions of Grenada and Panama or the 1992-1993 intervention in Somalia brutal into the outset category. In each case, presidents either cited a U.N. resolution as explanation for their actions (and powers) or simply acted without the express permission of Congress. Those three "modest" interventions cost the U.S. nineteen, forty, and 43 troop deaths, respectively.

In other cases, presidents notified Congress of their actions, but without explicitly citing section iv(a)(1) of the War Powers Act or its 60-day limit. In other words, presidents politely informed Congress of their intention to deploy troops and lilliputian more. Much of this hinged on an ongoing boxing over just what constitutes "state of war." In 1983, for example, President Ronald Reagan announced that he planned to send a contingent of U.South. troops to Lebanese republic, but claimed the agreement with the host nation "ruled out whatsoever combat responsibilities." Tell that to the 241 Marines killed in a later embassy bombing. When gainsay did, in fact, break out in Beirut, congressional leaders compromised with Reagan and agreed to an 18-month potency.

Nor was the judiciary much help. In 1999, for case, during a sustained U.S. air campaign against Serbia in the midst of the Kosovo crisis in the former Yugoslavia, a few legislators sued President Beak Clinton in federal court charging that he had violated the War Powers Act by keeping combat soldiers in the field by sixty days. Clinton simply yawned and pronounced that human action itself "constitutionally defective." The federal district court in Washingtonagreed and quickly ruled in the president'southward favor.

In the single exception that proved the rule, the system more or less worked during the 1990-1991 Persian Gulf crisis that led to the offset of our Iraq wars. A bipartisan array of congressional leaders insisted that President George H.W. Bush-league present an Authorization for the Use of Military Forcefulness (AUMF) well earlier invading Kuwait or Saddam Hussein's Iraq. For several months, across two congressional sessions, the House and Senate held dozens of hearings, engaged in prolonged floor debate, and eventually passed that AUMF by a historically narrow margin.

Even then, President Bush included a signing statement haughtily declaring that his "request for congressional support did non… institute whatsoever change in the long-continuing position of the executive branch on… the constitutionality of the War Powers Resolution." Snarky statements aside, sadly, this was Congress'due south finest hour in the concluding seventy years of nigh-constant global military machine deployments and conflicts — and it, of course, led to the state'due south never-ending Iraq Wars, the third of which is still ongoing.

Approving Enduring and Iraqi "Liberty"

U.S. soldiers encompass the face up of a statue of Saddam Hussein with an American flag earlier toppling the statue in downtown in Baghdad, Iraq. (AP/Jerome Delay)

The system failed, disastrously, in the wake of 9/eleven. But three days afterwards the horrific attacks, as smoke still billowed from New York'southward twin towers, the Senate approved an astoundingly expansive AUMF. The president could utilize "necessary and appropriate force" against anyonehe adamant had "planned, authorized, committed, or aided" the attacks on New York and the Pentagon. Caught up in the passion of the moment, America's representatives hardly bothered to determine precisely who was responsible for the recent slaughter or fence the best grade of action moving forrard.

Three days left paltry room for serious consideration in what was clearly a time for groupthink and patriotic unity, non solemn deliberation. The ensuing vote resembled those in elections in Third-World autocracies: 98-0 in the Senate and 420-ane in the House. Simply one courageous person, California Congresswoman Barbara Lee, took to the floor that 24-hour interval and spoke out. Her words were as prescient as they are haunting: "We must be conscientious not to embark on an open up-concluded war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target… Every bit we human activity, permit the states not become the evil we deplore." Lee was simply ignored. In this way, Congress's sin of omission set the stage for decades of global war. Today, across the Greater Heart Due east, Africa, and across, American troops, drones, and bombers still operate under the original mail service-9/11 AUMF framework.

The next time around, in 2002-2003, Congress proceeded to sleepwalk into the invasion of Iraq. Leave aside the intelligence failures and false pretenses under which that invasion was launched and just consider the role of Congress. It was a deplorable tale of inaction that culminated, just prior to the ignoble 2002 vote on an AUMF against Saddam Hussein's Iraq, in a speech that will undoubtedly prove a classic marker for the decline of congressional powers. Earlier a nearly empty chamber, the eminent Autonomous Senator Robert Byrd said:

"To contemplate state of war is to recall about the most horrible of human experiences… Equally this nation stands at the brink of battle, every American on some level must be contemplating the horrors of war. Notwithstanding, this bedroom is, for the virtually part, silent — ominously, dreadfully silent. There is no debate, no discussion, no attempt to lay out for the nation the pros and cons of this particular state of war. There is nothing.

"Nosotros stand passively mute in the United states Senate, paralyzed by our own incertitude, seemingly stunned by the sheer turmoil of events."

The bear witness backed upwardly his claims. Tardily on the night of Oct 11th, after only 5 days of "debate" — similar deliberations in 1990-1991 had spanned four months — the Senate passed a so-called war resolution (substantially a statement backing a presidential decision, not a congressional war proclamation) and the invasion of Iraq proceeded as planned.

Toward Forever State of war

Kurdish fighters from the People'south Protection Units, (Y.P.G), stand up guard next to American armored vehicles at the Syrian arab republic-Turkey border, Apri, 2017. (Youssef Rabie Youssef/EPA)

With all that gloomy history backside u.s.a., with Congress at present endlessly talking about revisiting the 2001 congressional say-so to take on al-Qaeda (but not, of course, the many Islamic terror groups that the U.S. military has gone after since that moment) and niggling revisiting likely to occur, is at that place any recourse for those not in favor of presidential wars to the stop of time? It goes without saying that in that location is no antiwar political party in the United States, nor — Rand Paul aside — are there even eminent antiwar congressional voices like Taft, Fulbright, McGovern, or Byrd. The Republicans are state of war hawks and that spirit has proven remarkably bipartisan. From Hillary Clinton, a notorious hawk who supported or argued for military interventions of every sort while she was Barack Obama's secretary of state, to quondam vice president and possible hereafter presidential candidate Joe Biden and nowadays Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, the Democrats are now also a party of presidential war making. All of the in a higher place voted, for instance, for the Republic of iraq War Resolution.

So who exactly tin can antiwar activists or foreign policy skeptics of whatsoever sort rally to? If more than lxx years of recent history is any indication, Congress but can't exist counted on when it comes fourth dimension to stand up, be heard, and vote on American wars. You already know that for the representatives who regularly rush to laissez passer record Defense force spending bills — as the Senate recently did by a vote of 89-9 for more money than even President Trump requested — perpetual war is an acceptable fashion of life.

Unless something drastically changes: the sudden growth, for instance, of a grassroots antiwar movement or a major Supreme Court conclusion (fat gamble!) limiting presidential power, Americans are probable to be living with eternal war into the distant future.

It'due south already an former story, but call up of information technology also as the new American way.

Top photograph | Servicemen of the "Fighting Eagles" 1st Battalion, eighth Infantry Regiment, walk by tanks that arrived via railroad train to the US base in Mihail Kogalniceanu, eastern Romania, Tuesday, Feb. xiv, 2017. (AP/Andreea Alexandru)

Major Danny Sjursen, aTomDispatch regular , is a U.S. Army strategist and sometime history teacher at W Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical assay of the Iraq War,Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge. He lives with his wife and 4 sons in Lawrence, Kansas. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet.

FollowTomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Alfred McCoy'due southIn the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.Due south. Global Ability, as well as John Dower'southThe Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War Two, John Feffer'southward dystopian novelSplinterlands, Nick Turse'southSide by side Time They'll Come to Count the Dead, and Tom Engelhardt'sShadow Government: Surveillance, Surreptitious Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

[Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial chapters, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.South. government.]

© Tomdispatch.com

![]() Republish our stories! MintPress News is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

Republish our stories! MintPress News is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

Source: https://www.mintpressnews.com/will-congress-ever-brave-enough-end-war-authorization/234143/

0 Response to "Will the Congress Ever Declare War Again"

Post a Comment